Posts tagged "university:":

A Cohesive Note-taking and Academic Workflow in Emacs

Why Emacs?

I have been using GNU Emacs for about three years now. I initially began using it after completing a semester of introductory programming classes exclusively in GNU Nano, with a series of shell scripts to compile and run C# code, and to set up a trio of terminals; one for code editing, one for compilation, and one to actually run the CLI program I was writing. I had practically created my own little system for terminal multiplexing. This might sound like hell, and in hindsight it was. I was not even aware of some of the abilities of nano to perform syntax highlighting, display line numbers, indent lines et cetera. I merely needed something quickly to write text in, and was horrified at my classmates who had to sit idly and wait for visual studio to start or restart after crashing, it did not help that visual studio was not even available in platform of my choice. In the beginning I only needed to write short programs, simple loops, input and output and the like, and so the simplicity of nano was not in any way a burden — in some ways it was even a boon due to its quick startup time and lack of clunky UI. But eventually I found it annoying having to create and resize my layout of terminals and writing long commands to get Microsoft’s Windows-centric tooling to compile on Linux became a chore. So I created little scripts to optimize my workflow. Nothing incredibly complex mind you, just little fixes here and there. When what is called “fall break” in Sweden came around I decided to ditch Nano entirely. I had friends who used Vim, but being a staunch hipster I decided I couldn’t copy them, at least not without trying the alternatives.

And so I started out with GNU Emacs. The approach of an environment I could extend in-situ, rather than having to deal with a multitude of different tools obviously appealed to me greatly, having done so earlier using shell scripts. I completed my assignments much faster than I was expected to, and used the extra time in class to read An Introduction to Programming in Emacs Lisp from within Emacs, making me more and more inclined to extend and shape Emacs to my own needs. Eventually I found out about org-mode and started to use it for very simple notes, quickly jotting down grocery list and project outlines. The big threshold came when I discovered the in-built functionality for \(\LaTeX\) exports. I had some early encounters with latex, but most of my knowledge was limited to what it was conceptually and how to write \frac{}{}. However, the default article class that is used when exporting from org-mode looks very nice, at least compared to what I was writing in LibreOffice or Google Docs. It is of course possible to get a similar quality in output from a WYSIWYG1 editor, but the amount of time you’d have to put in to do so is much larger than simply writing the text in org-mode and pressing C-c C-e l p. This of course does not have any impact on the quality of output, but as a fan of typography I like to think that a nicely formatted document enhances ones Aristotelian ethos, in that your credibility as a writer is improved in the eyes of the reader. Emacs therefore became relevant in not just my programming classes and microcomputer classes, but also all classes that involved some sort of essay or technical writing — Swedish, English, religious studies, history, engineering, and management. But there were two main subject that took up a considerable portion of my time where I had to put my cohesive Emacs workflow aside and resort to traditional techniques: physics and mathematics.

Mathematics in Emacs

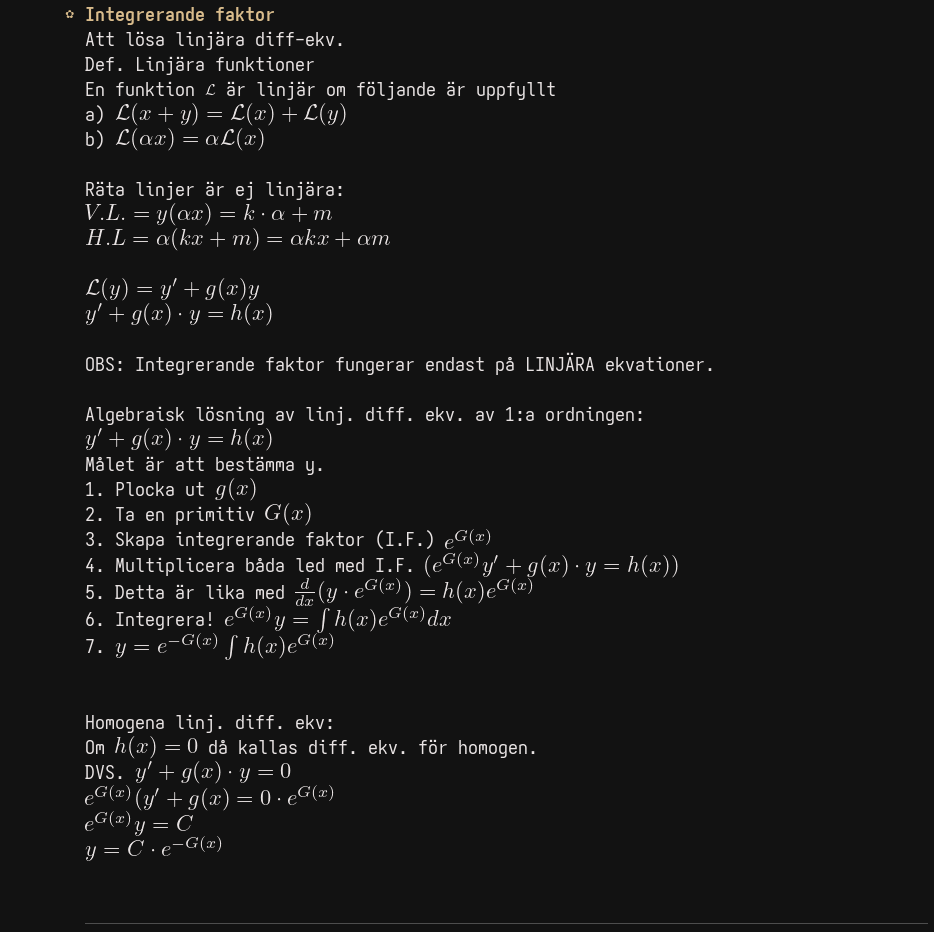

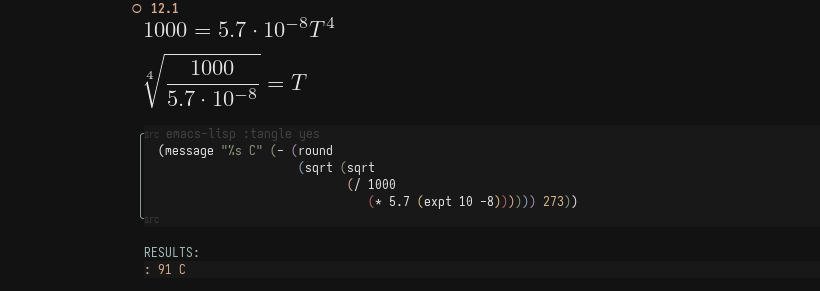

For taking notes I started out with a simple notes.org file, separating subject and topics organically with headers. I would recommend other to do the same. Initially, simply writing things down is the goal, and any optimisations will likely result in a net loss. I was inspired by Gilles Castel’s next-to famous series of blog posts on his note taking in LaTeX and vim, particularly his emphasis on “no delay [being] acceptable”. Of course, there are significant deviations in mine and Castel’s approaches and, to be perfectly honest, I think his notes are of a far superior quality. The primary difference is in medium; while the mathematics are written in latex, I prefer to write prose in the much lighter syntax of org mode or markdown, no \emph for me. Instead, I use org-latex-preview and org-fragtog to display latex inline and use the org documents themselves as notes instead of exporting them to PDF. Here is an example of a quick step-by-step way to solve first order differential equations using the integrating factor:

While Karthink has shown that you absolutely do not need to rely on writing snippets as Castel does, I still take that approach. Karthink relies heavily on auctex, an amazing suite for writing latex in Emacs, but most auctex functionality can not be used directly in org-mode. cdlatex, by the same author as org-mode, is however very useful through the org-cdlatex-mode minor mode. It allows for auto-completion of commonly written things like \(^{\text{super}}\) / \(_{\text{sub}} \text{-scripts}\) and Greek letters. It also creates a “just press tab whenever you want to continue writing” workflow that will move point in or out of delimiters and complete symbols. This combined with a liberal set of custom expanding templates using yasnippet creates a fast and coherent system since yasnippet also uses TAB as a key by default, meaning that you can spam it throughout writing, only thinking about the math conceptually as you’re listening to the lecturer.

But Emacs is not limited to writing mathematics merely in a documentary fashion, but also in a practical one. While theoretical mathematics operate on the syntax of math itself (algebraically), physics is often times interested in the actual values of the operations. For this I often quickly wrote mathematics in polish notation directly, also known as Emacs lisp. I find algebra difficult in polish notation, and so I usually do it in latex first, only performing the last numerical calculation in lisp.

This is what I would call the “killer app” of org-mode compared to other note taking applications like obsidian or pure TeX files. Being able to instantly tap into a programming language is really powerful, but it also feels very powerful, even when doing trivial things. Quickly being able to jot down numerical calculations (and having them written down for future reference) is quite useful. While I am sure one can write notes in Jupyter notebooks and other computational documents I have yet to hear of someone do this2. Emacs’ configurability means that one can easily adapt it to one’s own needs rather than either writing your own incomplete tooling or learning someone else’s workflow.

Humanities and the social sciences

After high school I have taken a break from the hard sciences and studied a few different subjects at Stockholm University and the Swedish Defence University. What strikes me as fundamentally different is that while mathematics builds on itself very clearly, where you directly use earlier knowledge to explore new topics, the social realm is a lot more “flat”. One can jump directly into Foucault’s postmodernism or Hegel’s Phenomenology and, while of course missing valuable context, still enjoy a degree of understanding. Comparatively it is quite difficult to get any sort of a grasp for quantum chromodynamics without firm knowledge of the structure of the atom. I also felt that studying depended much more on obtaining a breadth of ideas and perspectives rather than sitting down and mastering whatever new topic the lecture had covered. This then called for a radically different approach.

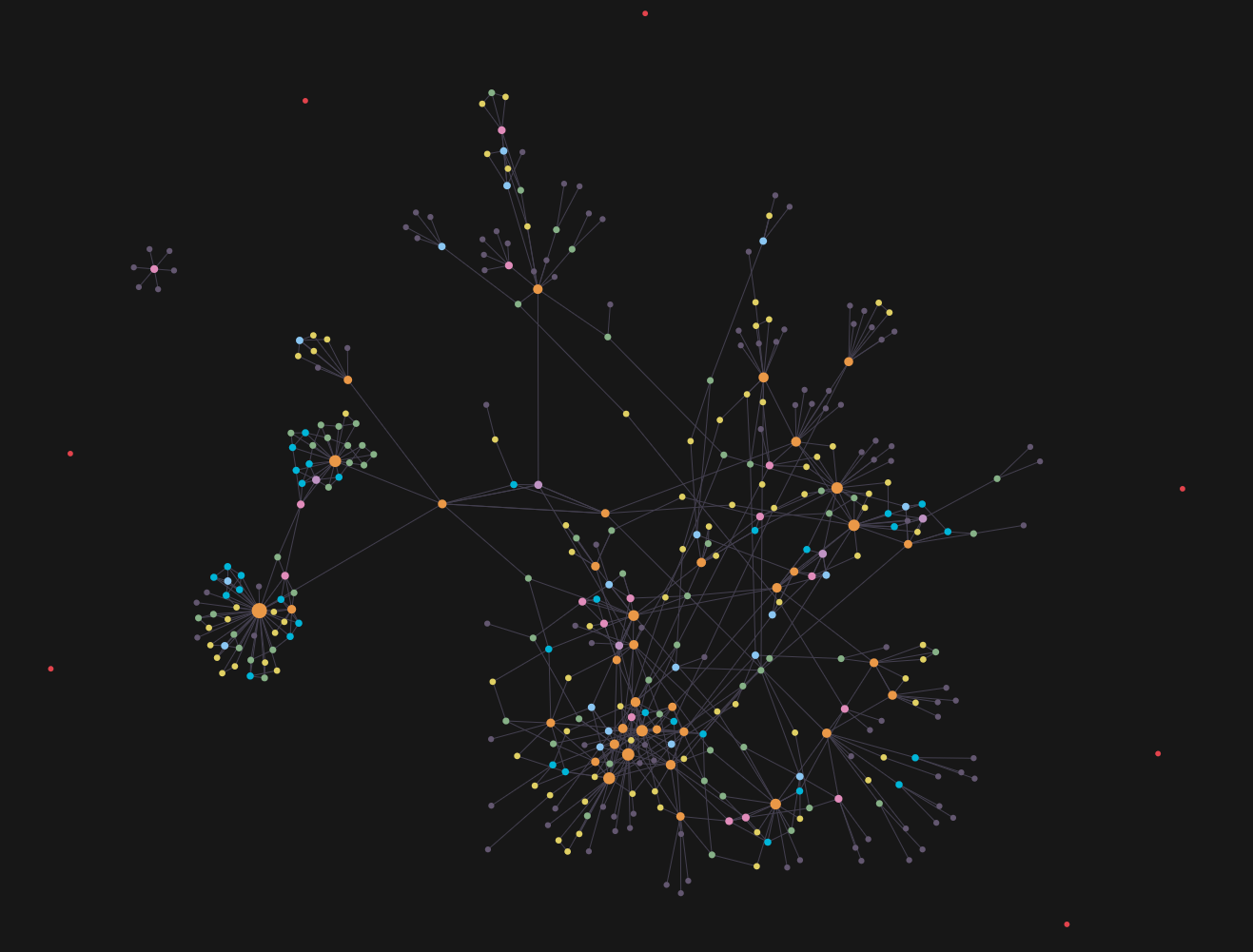

I ditched my former monolithic “one large file” approach and instead, somewhat reluctantly I admit, began using Org roam. I was critical toward the preaching I observed being done by users of various Zettelkästen systems and felt like the idea of a “second brain” encompassing all your knowledge were useless. Having used the system for almost a year now I still feel the same way. It is quite useful to be able to link ideas, since broad concepts and actors often show up in multiple areas3.

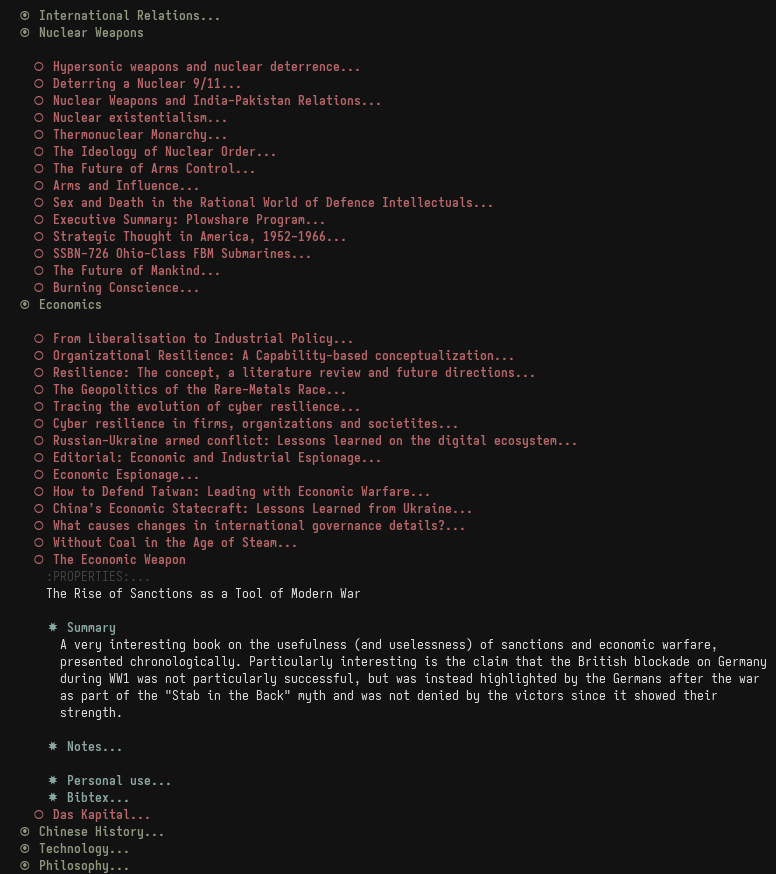

I also took inspiration from Gregory Stein to create an org-mode bibliography that combines notes of books and articles with their respective bibtex entries. Here I am back to the monolithic file approach, with each book or article read merely separated into different broad categories4. I have quite a backlog of saved .pdf files that I would like to convert to this new bibliography, but I do not have the time to do it all manually. To start I instead just asked an LLM to convert my hand-written citations for coursework into bibtex entries and sorted them into the file. I will let it grow organically from there.

Deliverables

Academia is in the end a forum for the exchange of new ideas, and the most efficient mode for the spread of ideas is text. While we may see some change in the structure of academic writing, particularly for those less experienced, as a result of large-scale LLM usage I doubt that text will be dethroned as the primary mode of communication for human society, but this is really a subject too deep to cover in a text about using Emacs as a student. For the time being writing reports and essays is still relevant to one’s daily life. I of course do this in org-mode, simply adding some latex headers to the document when I am done:

title: The Meiji Restoration and Modernisation of Japan subtitle: IR1.1 Seminar 1 Preparatory Assignment author: Joar von Arndt

For longer assignments I usually use a two-column layout. I tweak the values for the margins when I am done writing and ready to submit or print so that the text nicely fits the page, since I think it looks more “complete” and planned out that way. Otherwise I just write plainly in org-mode, using footnotes for citations.

Group work

I do not have a good system for incorporating this to group work, since most people do not know org-mode (or even markdown!) and collaboration in real-time can be tricky. If I worked with technically minded people I might use git, but even it requires some setup and work. Instead I use — and would recommend others do too — Typst, and its corresponding web app typst.app. It has easy collaboration, beautiful real-time previews for all users and most importantly of all, a markup that is far nicer than latex’s. I used it for my gymnasiearbete (diploma project) and found it to be a lovely experience. I would recommend anyone thinking about using overleaf or the like to instead use typst. The only reason I don’t do the same is because I still prefer the syntax-light approach of org-mode.

For presentations I am a fan of suckless’ sent, both because it places emphasis on me as the presenter but also because you can create presentations ludicrously fast. That allows me to iterate quickly and spend more time thinking about the actual content rather than fiddling with what’s going to be on the screen behind me.

Conclusion

Emacs is a tremendously useful tool, and I hope that this either serves as a motivation for beginning to use Emacs (showing of what can be done in it) or to inspire someone else to take inspiration in their own daily activities. I was prompted to writing this by Daniel Pinkston’s talk at EmacsConf 2024, and saw an earlier version of myself in him. I particularly want to emphasize that one approach does not fit all, not even when it comes to personal preference. Some lifestyles/subjects require different techniques, and so you should both experiment and iterate continuously to see what works for you. This is in-line with the Emacs philosophy of complete and instant extensibility, and so I therefore could not imagine a better platform to be writing or taking notes in.

Footnotes:

What-you-see-is-what-you-get

Are you someone who does this? Feel free to email me about this and tell me about your workflow, I am always interested in hearing how other people perform these tasks.

Like Marxism! Is there any field where there hasn’t been an attempt at the application of Marxism? There’s even Marxist mathematics.

Each entry does however have an org-id so that it can link and be linked to by other org-roam nodes.

The Role of Geography in Dynastic China

This post was written as an examination in the Premodern History of China, a course I took at Stockholm University, and is available as a PDF here.

Throughout Chinese history, there have been two great divides. First, that of the east-west, and later the north-south. These two dynamics have been instrumental in how Chinese society looks today and of how the history of imperial and premodern China played out. While China has had contacts with the outside world since time immemorial, it has been isolated from the outside world due to its geographic boundaries. To the north, large steppes and desert that makes settled agriculture largely impossible, as well as major mountain ranges. The west has large deserts and the major obstacle of the Tibetan plateau in the south-west, and further to the south tropical forests and a dense network of mountains. Finally, to the east lies the world’s largest ocean, the pacific, with only the islands of Japan and Formosa, as well as the Korean peninsula before a reaching expanse. These borders have shaped the Chinese frontier, but a multitude of geographic features have also impacted the Chinese interior.

The concept of the Chinese state originated in middle Huang He, where it merges with the wei river. The city of Chang’an served as the capital for numerous early Chinese dynasties such as the Zhou, Qin, Han and Sui dynasties due to its location in the easily defensible and fertile wei river valley. The north’s intermittent rainfall allowed for early irrigation systems that required more advanced social organisations1 and a more centralised form of rule. When engineering techniques improved, this allowed the fledgling northern states to expand beyond the narrow valleys of Shanxi out into the north China plain, probably the most well known geographic area of China. It, as well as the areas around it such as the Shangdong peninsula, form the basis of northern China, where the major food crop is historically wheat or millet and whose geography is dominated by the large alluvial plain created by the sediment-heavy Huang He2. This region was the agriculturally productive heartland of China for a long time due to its fertile Loess soil that could easily be exploited using relatively primitive techniques3, and the region conquered by the Emperor Qin Shi Huang when he first unified all of China. The later capital city of Luoyang is more exposed, laying east of Hanguguan, but was also closer to the economic center of the country. The balance between the strategic positioning of the capital in times of war and the needs to supply it in times of peace are significant forces that shaped the location, as well as the fate, of different dynasties’ power bases.

In contrast to the north, the south is mountainous and wet; the primary food crop is rice and the population is concentrated along narrow river valleys4. The main river is the Yangtze, the longest river in Asia, and the border between north and south runs along the Qinling mountains and Huai river. The Huai river has had a large strategic importance for any northern power wishing to conquer the south, and for any southern power wishing to protect itself against the north, as the many tributaries of the Huai flowing from the north mean that the north can easily amass a navy and sail it down the Huai into the Yangtze, threatening the power bases in places such as Nanjing. This is one of the major passes from north to south, the other being taking the Han river into the Yangtze, passing the city of Xiangyang, from the west. When the Song dynasty retreated south, becoming the southern Song, they did so behind this Qinling-Huai line and created a powerful standing fleet that managed to protect them against the numerically superior Jin-dynasty fleets in 1161 AD. The western approach was taken by Cao Cao — the general and prime minister whose deeds are described in The Romance of the Three Kingdoms5, after he had unified northern China, but he was defeated at the battle of the red cliffs, partly due to the narrow valleys and long supply lines of the Han.

The difficultly of travelling north-south compared to travelling along the Huang He or Yangtze and their tributaries in the east-west axis means that there was developed a distinct cultural boundary between the two. As early as the Romance, Sun Quan quipped “So the southerners can’t ride, eh?”6. Extensive attempts to connect these two regions, and to unite them under the banner of the Emperor were made to fit under the idea of Tiānxià — all under heaven. Chief of all was the construction of the grand canal, connecting the economically productive regions of the Yangtze to the capitals protecting the northern frontier at Luoyang and Beijing. This enormous project was especially useful to the Yuan and Qing dynasties as they could supply the enormous needs of their capital at Beijing while still remaining close to their power bases in Mongolia and Manchuria respectively. The grand canal served to connect what Wittfogel called “economic-political kernel-districts”7 that shaped Chinese statebuilding.

The interplay between geography and the historical trajectory of dynastic China highlights the significant role that physical landscapes play in shaping societal development. The unique agricultural practices, cultural identities, and political frameworks arising from geographic divisions have impacted the form and path of ancient China. An understanding of these geographical impacts is essential for a comprehensive appreciation of China’s multifaceted history and ongoing narrative, as they illuminate the lasting legacy of the land in influencing the lives and identities of its populace. This geographic perspective is a key way to look into how historical legacies inform challenges and aspirations throughout the vast scope of premodern China.

Footnotes:

Ch’ao-ting Chi, “Key Economic Areas in Chinese History, as Revealed in the Development of Public Works for Water-Control”. (London: Allen and Unwin, 1936), xxiv + 168.

George B. Cressey. “The Geographic Regions of China”. Worcester: Clark University.

Owen Lattimore, “An Inner Asian Approach to the Historical Geography of China”. Walter Hines School of International Relations: Johns Hopkins University. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1789948

G.B. Roorbach. “China: Geography and Resources”. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 39, China: Social and Economic Conditions. 1912. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1012079

Luo Guanzhong, “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms”. Translated by C.H. Brewitt-Taylor. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide Library. 2013. https://archive.org/details/romance-of-the-three-kingdoms-ebook

Guanzhong, “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms”. 1074.

Chi, “Key Economic Areas in Chinese History, as Revealed in the Development of Public Works for Water-Control”. 1.

The Philosophical Impacts of Nuclear Weapons

Similarly to this earlier post, this was written as an examination at the Swedish Defence University. It was written for the course Nuclear Weapons in International Security and as such is also available as a PDF here.

To answer the question of whether or not the invention nuclear bomb has been the most important event of human history is not an easy task. There are certainly numerous arguments in favour of such a statement; nuclear weapons have given us the thermodynamically most efficient form of releasing energy yet devised; they have given us the ability to quickly and easily destroy the major feats of our ancestors and possibly even those of our descendents; they have given us power beyond humanity’s comprehension. And yet the nature of a question of this broad a nature requires us to think more deeply about technological evolution and of our place within it. What constitutes an invention, and what makes certain inventions more important than others? Have the impacts of nuclear weapons, on both our materialist world and the cultural spiritus mundi, been large enough to warrant such a description? The Manhattan Project, despite its tremendous success from seemingly out of nowhere, was not a gift of Prometheus. The project itself was an industrial effort of incredible proportions, and built upon the recent cumulative advances in nuclear physics, quantum mechanics, and special relativity. It is therefore difficult to see the invention of nuclear weapons as a being a particularly important event from the left-handed qua limit perspective, while for those looking in from a right-handed perspective may see the Trinity test as a defining point in human history, especially given the role in the popular consciousness nuclear weapons were given during the cold war.

Nuclear weapons are fundamentally a tool for destruction. The term often used, the bomb, signifies its place as the ultimate explosive, whose Ding an sich is destructive potential in the extreme. They are the ultimate tool of our modern industrial society when organised for murder. It allows for the quick, easy, efficient, and large-scale genocide of the human race. It is hardly necessary to produce a bigger explosive, only delivery systems can be improved. The power to destroy has been concentrated as much as it ever could. The fate of all mankind is now concentrated in one decision, made by one man1. And yet the technology and industry involved is enormous. There are right now 21702 sailors dedicated to staffing American nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines, spending great lengths of time under the waves ready to strike at any moment. Airbases are filled with pilots and planes ready to be armed, and a massive system of Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) launch bunkers wait in silence. All this is then supplied and organised, and an enormous technological machine is used to communicate relay information between them and the President of the United States. Can the individual sailor, pilot, telecom operator, truck driver, or taxpayer feel any remorse over their part in this system of death? Not even the person most clearly responsible can, as Truman, the only man who has ever ordered nuclear weapons to be used on a fellow man, supposedly did not have any ’pangs of conscience’ in the slightest3. Each person involved has become alienated from the act of mass murder.

The subject that drives this development is that of technique, strictly different from that of technology. Jacques Ellul dedicates an entire chapter of his work La Technique ou l’Enjeu du siècle to trying to accurately define technique, and so summarising it here is difficult. But Ellul later uses a quote he sees as symptomatic of technique related to nuclear weapons.

We may quote here Jacques Soustelle’s well-known remark of May, 1960, in reference to the atomic bomb. It expresses the deep feeling of us all: “Since it was possible, it was necessary.” Really a master phrase for all technical evolution.4

Nuclear weapons were a logical next step after the discovery of nuclear fission and of its possibility for chain reactions. The scientific and engineering challenges that had to be overcome for the peaceful use nuclear fission were very similar to those involved in the creation of an explosive device5 (Perhaps with the exception of the development of exploding-bridgewire detonators for implosion-type weapons). The linear idea of progress toward efficiency means that a power source as efficient qua thermodynamics as the exploitation of the weak force was inevitable as a solution. Since it was possible, it was necessary.

But technique does not rest, it is ever expanding. The problems that followed the invention of the atomic bomb were not yet of a truly existential nature. While nuclear weapons were incredibly effective, they could still be reasonably defended against through the maintenance of air-superiority, and the requirements of large amounts of fissile material meant that they remained a scare tool. Ideas of nuclear weapons as simply more efficient bombs were not unheard of within the U.S. military establishment6. But the development of the thermonuclear bomb, with its orders of magnitude larger explosive potential and much smaller costs, created a true technical crisis. These fusion devices, placed atop ICBMs, allowed for the large-scale killing of entire nation states and continents. But more importantly, they were practically impossible to defend against. You no longer had to defeat your opponent militarily in order to coerce your opponent’s civilian population7. War became totally disconnected from both industrial capacity and military techniques. It also became possible for your opponent to strike back after you had launched your nuclear weapons, bringing both sides to a quick and grisly demise. To use the to use the terminology of Bueno de Mesquita8, nuclear weapons had destroyed the hope of any expected-utility that could be gained in any war involving them. This problem of course meant that the only rational use of nuclear weapons was to not employ9 them in a deadly conflict.

The invention of arms control is a technical invention to do nothing. The rational answer to the inquiry of nuclear weapons is to never detonate them, as in doing so the threat behind them becomes useless. But the industrial nations that have developed nuclear weapons — as well as the systems to maintain employment and constant readiness — can not readily give them up, only reduce their number. The answer to the self-inflicted problem of the uncontrolled nuclear arms race is then another solution, that of arms control. But this causes more problems; how to ensure compliance, the labour and organisation for monitoring stockpiles et cetera. A reason for the failure of the “five recognized nuclear weapon states” in fulfilling their obligations under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) and also the reason that the non-nuclear states do not feel betrayed over the nuclear armed states’ failure at disarmament may be that they themselves would feel pressured to keep their nuclear weapons had they possessed them. Why South Africa did give up its weapons was because it did so through technique. South Africa did not leave its nuclear weapons program in disrepair, but decided to decisively rid itself of its limited number of weapons in exchange for improvement of international relations and prestige. The technical use of nuclear weapons were in this case their destruction not in explosive form, but in dismantlement.

Carol Cohn has described her experience with what she has christened as technostrategic thinking by defence intellectuals regarding nuclear strategy. She sees it as “based on a kind of thinking, a way of looking at problems — formal, mathematical modeling, systems analysis, game theory, linear programming — that are part of technology itself”10. This line of thinking that Cohn identifies is not unique to the study of nuclear strategy, but is present in nearly every field today. Every example of this form of thought she mentions is a form of pure logical and theoretical reasoning, perhaps the purest example of a form of action driven by technique. Everywhere in our modern society there is a movement toward formal rational thinking that serves to effectivize all aspects of life and society, but perhaps most clearly the trio of land, labour, and capital. The specialized language Chon describes that acts as a barrier against uninformed opinions and outside criticism10 is also a symptom of technique. Each sector of life becomes increasingly obtuse and specialized, to the point of being totally enigmatic to an outsider to the field. The terminology used by defence strategists (Reëntry vehicles, countervalue, exchanging warheads et cetera) are of course descriptors of specific things (Not all vehicles exit the atmosphere and so only some reënter, countervalue contra counterforce, a mutual attack) but they also serve as a way to shape discussions qua Sapir-Whorf. There is of course no malicious intent behind this; it is merely the consequences of an increasingly technical field. Abstractions necessarily increase when detail increases, and so the expert is removed from the subject matter in some sense, the nuclear strategist no longer thinks of the horrors of nuclear war, of searing flesh and silently deadly radiation, but instead sees the subject through the eyes of countervalue, acceptable casualties, and mutually assured destruction. This is why those advocating for the total abolition of nuclear weapons are seen as malinformed activists, rather than subject matter experts. Because in some sense, they are. Becoming one of “them” requires adopting this language, and therefore the technostrategic thinking as Cohn also realizes.

Is there then no hope of stopping this technical development? It the only choice a nihilistic submission to its whims? This is not a particularly strange conclusion; technique is an inherently alienating force that removes meaning from not just our actions, but even our very lives themselves. What is the point in living on if your only accomplishment would be the continued advancement of an unsaid structure of society to which there is no alternative? Nietzsche was right in asking “Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?” in reference to our murder of God. Humanity needed to take God’s place because God did not give meaning to our lives any more. Instead the goal, the temple of human society, would be this tower of Babel. We would become masters of the physical world; “nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them”11. We set out to control our surroundings absolutely, and through technique we had no choice but to do so. If technique is superhumanly powerful and leaves us no agency in human development it may be easy to fall into nihilistic lines of reasoning. But nihilism is inherently unstable, since according to Kojève the nihilist

[…] disappears by committing suicide, he ceases to be, and consequently he ceases to be a human being, an agent of historical evolution.12

Kojève is not alone in this line of reasoning. Camus also agrees with this idea of the nihilist only having suicide as a true course of action13. In this void created by nihilism, existentialism finds its home. If we are genuine free beings we do have an ability to rid of our nuclear weapons, and every day choose not to. This then would be a source of existentialist angst over nuclear weapons, we do not only feel anxious over our possible demise due to their employment, but also over our moral failures at global disarmament.

The foundations of deterrence theory shares some similarities to the Kojève’s interpretation12 of Hegel’s Master-Slave dialectic14 where the masters (in this case the nuclear powers) fight for self recognition by competing in a struggle with other masters. Nuclear-armed nations joust in a game of brinkmanship, needing the other to back down. This is necessarily a fight to the death for self-consciousness. However, if both parties refuse to back down and annihilate each other that is clearly a loss for both sides. And in the other alternative of one side dominating the other absolutely and killing them, there is no one left to recognize the victor for what he has done. In other words, if there are two Americans and zero Russians left alive, we lose15. To achieve recognition one of the parties must necessarily back down and recognize the master as human, and become the slave. But as the master then stops recognizing the slave as human, he looks onward to other masters whom he sees as worthy of loving him. This constant cycle of struggle for the master is what causes stability on different levels within the nuclear system (U.S.-Russia, India-Pakistan, India-China). Neither side is willing to back down because they require this prestige to continue to legitimise their existence as nation-states.

This dynamic underscores the paradoxical stability created by mutual recognition of the destructive potential inherent in nuclear deterrence. The system persists not because it ensures peace, but because it creates a deliberately uneasy equilibrium16. As each nuclear power seeks to maintain its position as a “master,” it must engage in a delicate dance of demonstrating strength without triggering catastrophic escalation and risking destruction of the enemy it wishes to dominate. The recognition of mutual vulnerability — the “balance of terror” — forces adversaries into a perpetual state of brinkmanship, where neither side can afford to appear weak nor escalate beyond the point of no return. In this sense, nuclear deterrence aligns with Kojève’s existential reading of the Master-Slave dialectic: the master’s identity depends on the slave’s recognition, just as the credibility of a nation’s nuclear posture depends on the adversary’s acknowledgement of its willingness and capacity to retaliate. However, this precarious balance also breeds a deep-seated insecurity. A constant need for recognition requires equally constant displays of power — missile tests, military exercises, and rhetorical escalations — further entrenching the cycle of competition.

So if the development of nuclear weapons can be adequately explained by the march of technique and the actions of nations states be modelled as the struggle between masters, what then are the future developments of nuclear technology, and what impact has it made or will it make on human society or man in microcosm? In the event of catastrophic and cataclysmic nuclear war, a total war, that risks the extermination of the human species, the progress and continuity of history ends absolutely. Technical and industrial society will have destroyed itself and any future developments we might be interested in. We are then only interested in the existential dread that unemployment of nuclear weapons brings to people, or the effects of a limited nuclear war. A limited nuclear war is either the same as a total nuclear war, for the victims, or not too dissimilar as nuclear testing or a conventional war for those who survive. A limited war is mostly different in the restrain of the absolutist monarch, to use the language of Scarry1. The subjects of the nation state have no say in whether a total or limited nuclear war is waged. For these reasons, it is mostly of interest to analyse the dread of potential employment.

The state that backs down becomes the slave. And since the slave is no longer obsessed with this struggle for recognition in the nuclear arms race his now submissive population is terrified by their incapacity to fight against the adversary; The are struck by the fear of death that made them back down to begin with. It is this fear that Jaspers describes as an enlightened fear17, a constant imposing fear, that will drive human development and society toward a future that can handle the prometheisches Gefälle18 of nuclear weapons. The enlightened fear Jaspers describes is not just an individual or collective apprehension; it is a force that reshapes the structure of civilization. This fear drives humanity to seek ways of containing its newfound power, not through transcendence but through regulation, negotiation, and a constant reëvaluation of the precarious systems it has built. Yet this enlightened fear has a dual nature: while it can motivate coöperation and the pursuit of stability, it also perpetuates anxiety, creating a society perpetually on edge, defined by its ability to annihilate itself. If humanity can control this fear without resorting to the shackles of technique it will get the chance to become free in a way never before seen, but it also risks falling further into its clutches. In this framework, humanity’s potential freedom hinges on its ability to navigate the tension between its mastery of destructive power and the enlightened fear that compels its restraint. Kojève’s dialectical struggle, paired with Jaspers’ notion of enlightened fear, reveals a profound paradox: the tools of annihilation that could spell humanity’s end also serve as the catalyst for a collective awakening to its fragility and interdependence. This awakening, however, is not a singular event but an ongoing process — a process combining between the fear of extinction and the aspiration for a more stable, coöperative world order.

This dynamic reflects broader existential questions about freedom and control. What the master-slave dialectic teaches us the nuclear age transforms into a global condition. Nations, like individuals, are caught in a perpetual state of self-definition, reliant on both the acknowledgement of their peers and the restraint of their adversaries. The enlightened fear becomes a paradoxical source of empowerment, as it fosters a new kind of freedom: the freedom to act responsibly within the constraints of mutual vulnerability. This is the core idea behind arms control, that stability within this shared vulnerability will cause both fear, the fear to act, and enough security that both sides can focus on other matters within this fear. This balance between fear and security is what makes arms control a crucial mechanism in the nuclear age. By fostering stability through mutual agreements, arms control seeks to institutionalize the enlightened fear, transforming it into a structured and predictable element of international relations16. This does not eliminate the fear but channels it into a framework where its intensity can be managed. Stability arises not from the absence of tension but from the creation of systems that make escalation less likely and ensure that even in moments of crisis, the costs of catastrophic action remain prohibitively high.

The interplay between fear, control, and power in the nuclear age brings into question not only humanity’s technological and political evolution but also its moral and philosophical trajectory. The existential implications of nuclear weapons extend beyond the realm of international relations and into the core of human identity, autonomy, and survival. Nuclear deterrence, while maintaining an uneasy peace, amplifies humanity’s existential tension. The omnipresence of annihilation redefines freedom — not as liberation from constraint but as the capacity to exercise restraint in the face of overwhelming power. This reframing challenges the Enlightenment and technical ideal of progress, which envisioned technological advancement as a pathway to emancipation. Instead, nuclear weapons exemplify technique in that they shackle humanity to the perpetual threat of its own destruction. This tension resonates with Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence19: the idea that humanity might be condemned to relive its choices endlessly unless it finds the courage to affirm them fully. The nuclear dilemma forces us to grapple with the ultimate recurrence — living perpetually under the shadow of weapons we have created but cannot fully control. The choice, then, is not between employment and non-employment but between continued existence within this precarious balance and a radical reïmagining of what human progress entails. It is this choice that compels Sartre to see nuclear weapons as a liberator, that the conscious choice of nuclear weapons requires us to “every day, every minute, […] consent to live”20. We choose to maintain our arsenal of weapons in order to be granted this enlightened and authentic fear. If this fear will be a constant necessity or not is unclear, the use of nuclear weapons may perhaps be transformed by a global superstate into a tool for something other than death21. The dominance of technique makes it unlikely to lead to the total elimination of nuclear explosives however.

Achieving such a reïmagining requires more than disarmament. It demands a cultural and philosophical shift — a collective recognition that humanity’s worth is not tied to its capacity for domination or destruction but to its ability to foster creativity, love, and goodness in the world. This transformation parallels the existentialist call for authenticity; In that we should strive to live as we are innately. But this can only be driven by Jaspers’ enlightened fear, mirroring Mencius’ need for education to act morally. Heidegger sees this as a crucial point of technique, that “Unless humanity makes an effort to reörient itself, it will not be able to find revealing and truth”22. The nuclear age, then, is not just a historical epoch but a crucible for defining what it means to be human. It forces us to confront the duality of our nature: our capacity for boundless creativity and our potential for unparalleled destruction. Whether humanity can transcend this duality — or whether it will succumb to the very forces it has unleashed — remains an open question. But the answer lies not in the weapons themselves but in the choices we make about how to live with, and ultimately move beyond, their shadow.

The nuclear age compels humanity to confront the duality of its existence — its unparalleled capacity for both destruction and creation. The challenge is not merely technological or political but profoundly existential: to reïmagine progress and security in a way that transcends the pursuit of power and embraces a vision of collective flourishing. This transformation demands a conscious reckoning with the ethical responsibilities of wielding such destructive potential and a commitment to embedding restraint and cooperation at the core of global civilization. Ultimately, the legacy of nuclear weapons will be defined not by their use or disuse but by the choices humanity makes in their presence. These choices reflect the broader question of what it means to be human in an age where the tools of annihilation coëxist with the potential for boundless creativity. Whether we succumb to the nihilism caused by our inventions or rise to the challenge of building a new world remains an open question, but the stakes could not be higher. The future of humanity hinges on its ability to live authentically and wholly under the shadow of this technical evolution.

Footnotes:

Elaine Scarry, “Thermonuclear Monarchy: Choosing Between Democracy and Doom”. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2014.

Federation of American Scientists. “SSBN-726 Ohio-Class FBM Submarines.” Accessed 2024-09-10. https://web.archive.org/web/20240910141737/https://nuke.fas.org/guide/usa/slbm/ssbn-726.htm.

Günther Anders, “Burning Conscience”. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1959.

Jacques Ellul, “The Technological Society”. New York: Vintage Books, 1964.

Robert Oppenheimer, “Public Lecture by Robert Oppenheimer.” November 25, 1958. Accessed 2024-11-30. https://archive.org/details/public-lecture-by-robert-oppenheimer-11-25-1958.

Marc Trachtenberg, “Strategic Thought in America, 1952-1966”. Political Science Quarterly: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Tomas Schelling, “Arms and Influence”. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1966. 1-34. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt5vm52s.4

Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, “The War Trap”. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981. https://archive.org/details/wartrap0000buen/mode/2up.

The definition of the use of nuclear weapons is one that is not straightforward. Most nuclear weapon use has been either rhetorical (threats), or demonstrative (nuclear weapons testing). Both of these fall under the umbrella of “nuclear signalling”. The detonation of nuclear weapons on the population or military facilities of an enemy, like those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is one that I will in this text refer to as the employment of nuclear weapons. In this case \( Employment \subsetneq Use \).

Carol Cohn, “Sex and Death in the Rational World of Defense Intellectuals.” Signs 12, no. 4 (1987): 687–718. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174209.

Genesis 11:6

Alexandre Kojève, “Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit”. London: Cornell University Press, 1969.

Albert Camus, “The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays”. Translated by Justin O’Brien. New York: Vintage Books, 1942.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. “The Phenomenology of Spirit”. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

A reference to Thomas S. Power’s famous quote in response to a RAND counterforce strategy avoiding Soviet civilian targets:

Restraint? Why are you so concerned with saving their lives? The whole idea is to kill the bastards. At the end of the war if there are two Americans and one Russian left alive, we win!

Thomas Schelling, “The Future of Arms Control”. Operations Research 9, no. 5 (1961): 722–731. http://www.jstor.org/stable/166817.

Karl Jaspers, “The Future of Mankind”. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963. https://archive.org/details/futureofmankind0000unse.

Günther Anders, “The Obsolescence of Man, Volume II: On the Destruction of Life in the Epoch of the Third Industrial Revolution”. Munich: C.H. Beck. 1980. https://files.libcom.org/files/ObsolescenceofManVol%20IIGunther%20Anders.pdf

Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Gay Science”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1882.

Jean-Paul Sartre, “The Aftermath of the War”. Oxford: Seagull Books. 2008. https://archive.org/details/aftermathofwarsi0000sart

The U.S. Department of Energy, “Executive Summary: Plowshare Program”. Accessed 2024-11-30. https://www.osti.gov/opennet/reports/plowshar.pdf

Martin Heidegger, “Die Frage nach der Technik”. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann. 1954. https://monoskop.org/images/2/27/Heidegger_Martin_1953_2000_Die_Frage_nach_der_Technik.pdf

A Historical Perspective on Strategic Resources

This text was originally written as an examination at the Swedish Defense University (Försvarshögskolan) for the course in Economic Security in Competition, Conflict and War and is therfore available as a PDF here.

Throughout the history of human civilization, the characteristics of strategic resources and the methods of dealing with them have changed considerably. But as our economy becomes more and more complex, and the number of materials increases together with this complexity, the application of any single material represents a smaller and smaller portion of economic activity. For this reason, the impact of any single resource on the world’s supply chains is unlikely to have as significant of an impact as they might have had in the past. It is interesting however to observe how nations have dealt with the issue of strategic resources in the past and to learn how those techniques may be used in the future to protect critical industries. Historically energy has been the principal strategic resource, but in recent time the prodution of computing machines and information processing has become increasingly important.

For almost all of human history, the labour of mankind was almost entirely devoted to the production of food. Major disasters such as the collapse of Bronze Age civilizations three thousand two hundred years ago did not have insufficient bronze supply as sole cause, even if it may have contributed to the crisis1. Iron age societies were more self-sufficient, as iron is relatively plentiful around the world compared to the long and delicate trade networks bronze age civilizations required to obtain tin. It really took until the age of discovery for the empires of Portugal, Spain, and eventually the Netherlands and their attempt to dominate Southeast Asian spice production for a precursory form of the strategic resource to appear. This grew to become the world’s most important trade2, as the basic production of foodstuffs was still largely limited to subsistence farming and was therefore only locally disrupted by rare events like droughts3. Spice production and trade fueled Europe’s burgeoning empires. But by and large, since so much of the economy was distributed and focused on local matters, no resource managed to be impactful enough to accurately be described as a strategic resource.

With the advance of industrial manufacturing, more effective agriculture, and rapid urbanization, and most of all the use of sources of energy not reliant on human or animal labour led to the rise in complex supply chains and the use of rarer and more advanced materials. Following the demise of the Dutch Republic, the Spanish American Wars of Independence and the Napoleonic Wars, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland emerged as the preëminent leader in the world. It did so partly on the back of Watt’s steam engine from the late eighteenth century, it in turn fueled by long since exploited high-quality British coal. Other European great powers such as France, Prussia, and later Germany were all fueled by the large consumption of coal4, partly becoming the reason those powers eclipsed their rivals such as Russia4, the Habsburg Monarchy5, and Italy6. The later use of steamships required an extensive system of coaling stations and collier ships to facilitate global trade networks that became ever more interconnected during the first globalisation. As the nineteenth-century economist W.S. Jevons wrote in 1865:

Coal in truth stands not beside but entirely above all other commodities. It is the material energy of the country — the universal aid — the factor in everything we do. With coal almost any feat is possible or easy; without it we are thrown back into the laborious poverty of early times. 7

Coal thus became the world’s first true strategic resource, vital to not just the income of those who traded it, but critical to the stability of the entire nation’s economic health. Any nation, regardless of their location in the world or state of development, needed to acquire a steady and reliable supply of coal to avoid being “thrown back into the laborious poverty of early times”. But the eventual replacement of the steam engine by the internal combustion engine meant that the Europeans could no longer rely on domestic sources of energy but had to import foreign oil.

The start of the oil industry has its origins in Titusville, Pennsylvania, where the very first oil well was drilled six years before Jevons described coal as the universal aid. Oil was at first not a critical resource because it was almost entirely a product for illumination, competing with coal-based “town gas” and blubber from whales hunted at sea8. Pennsylvania was the Saudi Arabia of its time, and the United States produced the lion’s share of the world’s petroleum. But production soon started in other places around the world, and the Russian (today Azerbaijani) city of Baku became the primary supplier to European kerosene. The state of highly-developed globalisation that occurred in the late nineteenth century meant that large multinational companies could easily operate world-spanning distribution networks, and companies such as Royal Dutch, Shell Transport and Trading, and largest of them all the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey dominated the global oil industry8. This meant that while the UK had some presence in the logistical and distribution areas of the oil industry (so-called mid- and downstream in industry terminology) it did not possess any major oil fields known to the world at the time (and so did not have an upstream presence). This first became an issue when Winston Churchill (then the First Lord of the Admiralty, the political head of the Royal Navy) pushed for the transition from coal to fuel oil for the Navy’s ships. This was a strategically difficult decision, but needed to counter the German investment into their Hochseeflotte, as oil-fueled ships were technologically superior to steam powered ones8.

While Shell was a British company, it was dominated by the 60/40 merger with Royal Dutch in 1907 and was therefore chiefly in the control of foreign interests in the view of the British government, especially as Anglo-German relations grew more amicable at the turn of the century9. To create an entity that would prioritize the fleet in the event of a conflict the British government bought a controlling share in the struggling Anglo-Persian Oil Company that had used up nearly all of its capital exploring for oil in Iran. Anglo-Persian would operate as a privately owned company in practice, but would through its state-owned nature prioritize British customers, primarily those of interest to the security of the empire8. This is a very clear example of the state intervening to protect its position in a sector it deems as vital to the national interest. This arrangement had its obvious benefits, but was largely unnecessary. Royal Dutch Shell ended up being the primary supplier to the British during the first world war, and with the entry of the United States into the war the Entente oil supply represented close to all of global production8. While oil was useful during the great war, it had not yet reached its peak of usefulness in military strategy.

The rise of mechanized warfare and aviation that got its start during the first world war but really took off in the interwar period and during the second world war meant that oil became a truly critical commodity. The rise of the internal combustion engine and the mass production of the car at the turn of the century, meant that the oil industry had grown considerably. It had also saved it from the rise in electrical lighting during the same period that caused a severe decrease in kerosene revenues8. The Second World War cemented its status as the world’s most vital strategic resource. The German Blitzkrieg strategy, which relied heavily on mechanized units, was directly dependent on fuel supplies. This was the main driver for Fall Blau whose objective was securing the oil fields of the Caucasus. Writing on his experience on the African theatre of the war, the German field marshal Erwin Rommel said the following:

The bravest men can do nothing without guns, the guns nothing without plenty of ammunition, and neither guns not ammunition are of much use in mobile warfare unless there are vehicles with sufficient petrol to haul them around.10

Likewise, Japan’s expansion in the Pacific was driven by its need to secure raw materials, especially oil, as its own domestic supplies were virtually nonexistent. After the United States sanctioned Japan following its invasion of China, denying it the ability to buy oil, Japanese strategic planning became centred on the security of its oil supplies. Even after the conquest of the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) the Japanese remained afraid of American capabilities to intercept shipments of petroleum on their way back to the Japanese home islands. This was a core reason for the attacks at Pearl Harbour that brought the Unites States into the war. Even during the war, oil supplies were a constant struggle for the Japanese military. Despite attempts to make aviation fuel out of pine cones on massive scales, the Japanese air force was forced to carry out its famous kamikaze attacks principally due to shortage of fuel8.

Both during and following the war, large supplies of oil had been found in Arabia and in other places around the world. But despite the fact that oil had been proven to be perhaps the most important resource for mobile warfare, neither of the two superpowers saw oil supply as particularly worrying. This is because they both possessed some of the world’s largest supply and the nations where these new supplies were being discovered were either neutral or somewhat aligned with the two superpowers (Venezuela and the Soviet Union, the United States and Saudi Arabia11). Thus the question of fuel became more of a logistical challenge rather than where control of oil fields would be the objective of the war. The new petrostates saw oil instead as deeply critical to the economic health of their nations, and fought a long battle with the large Anglo-American oil companies (the so-called Seven Sisters) over the revenue split from the sale of oil. The Iranian nationalisation of the Anglo-Persian oil company, now renamed Anglo-Iranian, prompted the intervention of the British and American governments to topple the Iranian government in 1953. This was intended to maintain both adequate levels of supply to the west, as well as avoid a cascading effect of state seizure of Anglo-American oil companies around the Persian Gulf8. This shows one of the possible methods of action that larger states can use to secure the supply of strategic resources in foreign countries; exploiting the internal power struggles of different interest groups. This does however risk the ire of those groups you helped overthrow, and this was partly the reason for the Islamic Republic’s belligerent foreign policy toward the Anglo-Saxon nations, especially toward the United States.

But despite this lack of strategic interest oil’s significance only seemed to grow. Petroleum not only powered the world’s cars, airplanes, industry, and electrical generation, but was also being used in an ever increasing number of products on larger and larger scales in every sector from construction, to plastic packaging, to pharmaceuticals. This increase in demand coincided with a increase in the share of U.S. oil that was imported from foreign countries. This was exploited by the major Arab oil-exporting nations, who were aggravated by staunch western and U.S. support to the State of Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War8. They, through the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), refused to export oil to those nations who supported Israel. This led to an unprecedented rise in the price of crude oil and caused a global economic recession. However, while the Arab nations were successful in their use of tactics, their overall strategy failed. OPEC has not been able to control the world oil market in the same way since, owing to factors such as the increased fungibility of oil, diversification of supply12, and cheating by OPEC members on production quotas8. Since market economies are so resilient the effectivity of these instruments naturally decrease after they have been proven possible, as the actors implement de-risking and diversification strategies to limit the damage that they could potentially suffer.

The primary instrument created by the oil-importing industrial nations to tackle the immediate hold over the oil markets that OPEC had was the creation of the International Energy Agency and a system of oil reserves held by its member states that can be emptied as a reaction to jumps in the price of oil. Largest of these is the American Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which holds up to 714 million barrels of crude oil13 and can be used at the discretion of the American president. These global reserves of oil are not a substitute for domestic production, but they allow for increased mobility within the international system for the industrial nations and gives them the ability to punish nations that temporarily lower production. Oil can be stored quite cheaply within impermeable salt domes for a long time, connected to a preëxisting network of pipelines to quickly increase supply; it is a resource that is logistically very easy to store. As oil production became ever more decentralized and the amount of control individual actors decreased, the days of John D. Rockefeller setting prices across the world was long gone, oil became less and less strategic as supply disruptions still meant that it could be bought from somewhere else, even if at a slightly higher price.

It was during this period that oil started to take a back seat to the increasingly sofisticated computer industry. During the late 20th century the commodification of information, and the machines that processed it, became increasingly valuable. The invention of the transistor in 1947, the metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) in 1955, and later the integrated circuit (IC) in 1959 allowed the mass production of computing machines on an unprecedented scale. Moore’s law and Dennard scaling meant that computers not only became cheaper, they also became faster and used less power as the size of transistors decreased exponentially 14. Like oil, this industry is very capital-intensive and is used in every facet of the economy. Unlike the oil industry however, a nation does not need to posses any special resources to compete in the IC supply chain. This aspect was very attractive to some nations.

Critical to this nascent industry was the location of these companies to both acquire expertise and reduce labour costs. The early semiconductor was centred on “Silicon” Valley after Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory and its descendent Fairchild Semiconductor had pioneered the silicon transistor and integrated circuit, respectively. Since these early chips were more reliable due to their solid-state nature, their first large customer was the American military for use in the Minuteman-II ICBM. As the semiconductor industry grew, IBM emerged as the juggernaut. But the American dominance of the semiconductor industry was not to last. American efforts to offshore the “packaging” of chips meant that knowledge was continuously transferred overseas, particularly to the Four Asian Tigers of the Republic of Korea, Republic of China (ROC), Hong Kong, and Singapore; but also to the Philippines and especially Japan. The Japanese market was large and possessed a large number of companies manufacturing ICs and semiconductor components. The ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) wanted to maintain Japanese competitiveness to American penetration into their market by keeping up with the developments in “Very Large Scale Integration” (VLSI) technology that was needed for the ever increasing number of components used in any given IC14.

The LDP thus had a sophisticated plan to maintain the Japanese IC industry. To accelerate VLSI development the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) incentivized the otherwise intensely competing companies through free government loans that represented a much larger R&D expenditure than what any single Japanese company could afford, though much smaller than what the major American companies were investing in VLSI R&D15. Mark Shephard, the then chairman of Texas Instruments, commented on the funding of the VLSI project: “We can afford to bear, and do bear, such expenditure alone”15 showing how the amount of capital employed was not a critical reason of success in and of itself, but rather its effect of forcing the companies to coöperate was tantamount. The effect of the money was instead was a willingness to coöperate, to obtain R&D funding, rather than bolstering the amount of resources that the project had. The project had both experienced administrative and technical personnel, researchers from different companies all worked collaboratively in the same facilities on technologies that they would all benefit from, with a clear deadline and goal; to achieve Japanese VLSI capabilities before IBM computers utilizing the technology entered the Japanese market at the latest of 198015. The project was wildly successful and put Japan on parity with, if not ahead of, the United States in the fabrication of ICs15. It is worth noting that the identically named “VLSI Project” that started two years after the Japanese one in the U.S. that was also very successful focused on largely different challenges with VLSI and could perhaps be the reason for American dominance in software today, spawning things such as the Berkley Software Distribution (BSD)16, 32-bit workstations, and the CAD tools leading to the founding of companies such as Synopsis17.

The approach taken by the Japanese VLSI project shares some similarities with the recommendations made by Malmberg et al.18. While there was state expertise and resources employed in the project the main resources applied were private. This shows how the guiding hand of the state can effectivize the resources of private industry and also guide them into strategically important reasons for the state. Another, perhaps more famous, example is the founding of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). While the ROC had already been instrumental in the creation of another major semiconductor manufacturer seven years earlier, United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC), UMC was not fully prepared for the change in business model that was quickly becoming apparent19. TSMC was the first in was is now a series of companies in the “pure-play foundry” model. As the IC fabrication facilities (fabs) became more and more expensive and required higher and higher utilization rates newer design firms opted to pay larger companies, who had their own fabs20 to make their designs. But these companies were of course unprioritized as the companies preferred to make their own products. TSMC would never compete with their customers and did the job cheaper and better than the large IC companies did. While the government never held an outright majority in the stake of the newly founded company, it was and is the largest shareholder, contributing key capital and support at the beginning of the firm’s existence. The ROC also helped secure a technology transfer agreement with the major Dutch electronics manufacturer Phillips and ministers personally called wealthy Taiwanese businessmen to convince them to invest in this new venture. TSMC was neither a project purely created by the state nor a mere corporate enterprise. Rather it was a project of the Taiwanese society whose success or failure involved both state planning and vision as well as private sector expertise and resources.

This dominance in a critical industry is useful in achieving foreign-policy goals. ROC control of this middle ground in the IC supply chain meant that the they could use this choke point to plausibly deter a forceful reunification by the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Since dominance in IC manufacturing does not hinge on the control of a strategic geographic location, but rather delicate high-tech fabs and an equally brittle system of supply chains, an armed conflict could easily result in the destruction of these facilities and bring about large economic damages to both nations involved as well as the larger global economy. ICs are also much harder to store than oil as they are continuously updated and improved, with much of the knowledge not even written down but passed around through tradition and experience. Avoiding the upset of this thin balance is in the interest of every major economy on the planet today, and exerts enormous pressure on the actors involved. The PRC’s recent attempts at cornering the market for rare metals, particularly rare-earth metals, shares this strategic thinking. Rather than being able to completely stop production of advanced technology in hostile countries, a practical impossibility owing to the small volumes of these materials, the PRC uses increased economic inefficiency as a weapon to deter countries from intervening it what it deems critical foreign policy objectives (Such as the status of Formosa). The failure of economic warfare on impacting the overall quality of war materiel21 means that the shock tactics employed by China will do little other than undermine its monopoly in the event of a war over the Taiwan strait, like what happened with OPEC after 1973. Even those fearful of China’s ability to use these materials through coërcive means will admit that illicit trade and extraction of rare metals even directly with the PRC, not counting possible routes through third-party countries, is very possible11. So while these resources are critical for certain industries and perhaps even the economy as a whole, it is unlikely that the targeted embargo of these resources would cause wide-spread economic collapse like that seen in 1973 or spark some sort of military intervention like in 1991.

As technology advances, so too will the division of resources and techniques employed. The days when foraging, hunting, and fishing was all that humanity did to sustain itself at the dawn of humanity has long since passed, and with it the hope of complete self-reliance. The ever increasing list of goods seen as critical to the economy, like that published by the European Commission22 or the United States Department of the Interior23, shows how belief on how supply disruptions of specific goods can have outsized effects on the security of nations is widespread. This belief is not new, Jevons pointed this out in regards to coal in the middle of the 19th century, however the scale of those materials involved and the number of discrete ones is unprecedented. It is on such a level that any one nation or actor can not expect to control all sources of supply, but should rather attempt to specialize in a certain focus of industries in an attempt to maintain other countries’ willingness to trade, as the PRC has done with rare-earth metals. To maximize possible damage to a hostile actor, countries should aim to dominate industries that represent a large share of a country’s imports, either in terms of tonnage or dollars, since they would be difficult to replace. Since low-value manufacturing and primary resources are largely fungible, it is best to target high value-add technology sectors or services, as these have historically had an outsized importance compared to the resources ventured.

Footnotes:

Kemp, L., & Cline, E. H. (2022). Systemic Risk and Resilience: The Bronze Age Collapse and Recovery. In A. Izdebski, J. Haldon, & P. Filipkowski (Eds.), Perspectives on Public Policy in Societal-Environmental Crises: What the Future Needs from History (pp. 207–223). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94137-6_14

Laurea, T. (2021) Spices, Exotic Substances and Intercontinental Exchanges in Early Modern Times. Venice: Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia. http://dspace.unive.it/handle/10579/19714

Snyder-Reinke, J. (2009) Dry Spells: State Rainmaking and Local Governance in Late Imperial China. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center.

Fernihough, A., & O’Rourke, K. H. (11 2020). Coal and the European Industrial Revolution. The Economic Journal, 131(635), 1135–1149. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueaa117

Gross, N. T. (1971). Economic Growth and the Consumption of Coal in Austria and Hungary 1831- 1913. The Journal of Economic History, 31(4), 898–916. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2117215

Bardini, C. (1997) Without Coal in the Age of Steam: A Factor-Endowment Explanation of the Italian Industrial Lag Before World War I. The Journal of Economic History, 57(3), 633–653. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700113397

Jevons, W.S. (1865). The Coal Question; An Inquiry concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of our Coal-mines. London: Macmillian and Co. 2nd edition. pp. 14.

Yergin, D. (1990) The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power. New York: Free Press.

Sterenborg, P.J.C. (2016) The Netherlands and Anglo-German Relations. Utrecht University.

Lidell-Hart, B. (1953). The Rommel Papers. New York: De Capo press. pp 342.

Rossbach, N. (2023) Sällsynta metaller och stormaktsrivalitet: En översikt om nya strategiska resurser och risken för råvarukonflikter. Totalförsvarets förskningsinstitut.

The share of OPEC oil production has been eroded by the introduction of new producers or increased production in the North sea (the United Kingdom and Norway), the Canadian oil sands, the southern and eastern coasts of Brazil, as well as fracking in the United States.

Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response. (2024-10-21) Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Department of Energy. https://www.energy.gov/ceser/strategic-petroleum-reserve

Miller, C. (2022). Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology. Scribner.

Sakakibara, K. (1993). R&D cooperation among competitors: A case study of the VLSI semiconductor research project in Japan. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 10(4), 393–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/0923-4748(93)90030-M

The ancestor of today’s OpenBSD, FreeBSD, DragonFly BSD, and NetBSD.

One of the companies creating the modern-day duopoly in IC design, the other being Cadence.

Malmberg, P. et al. (2024) En ny beredskapssektor - för ökad försörjningsberedskap Statens offentliga utredningar 2024:19.

Hu, J. (2024) Taiwan’s transformation into global semiconductor leadership and future challenges. DigiTimes Asia. https://www.digitimes.com/news/a20240225PR200/taiwan-semiconductor-industry-subsidy-tsmc-umc-pure-play-foundry.html

“Real men have fabs” was a common saying at the time.

Mulder, N. (2022) The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War. Yale University Press: 27-108.

European Commission. (2011). Tackling the Challenges in Commodity Markets and on Raw Materials. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0025

Applegate, J. D. (2022) 2022 Final List of Critical Minerals. U.S. Geological Survey, Department of the Interior. https://d9-wret.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets/palladium/production/s3fs-public/media/files/2022%20Final%20List%20of%20Critical%20Minerals%20Federal%20Register%20Notice_2222022-F.pdf