The End of History.

Introduction

Francis Fukuyama is probably the person most connected to the concept of “the End of History”, but he is not the originator of it. Fukuyama’s intial article1 (that was then later expanded upon to the book The End of History and the Last Man) initially reads as a summary of the Kojévian interpretation of Hegel’s observation of the end of History. Fukuyama sees in the collapse of the Soviet order in eastern Europe as not just a victory of western liberal democracy, but as a showcase of this western system as the ultimate goal of human society entirely. This view of History ending seems to have been thoroughly debunked in our popular consciousness, to the point of simply naming the concept in my international relations class elicits chuckles across the lecture hall, and academic scholars praise Finland for “never [believing] that history ended in 1989”2. I have not read Fukuyama’s larger coverage of his thinking on this subject, only his initial article titled The End of History? as well as the original sources of Hegel’s Phenomenology and Kojéve’s lectures on it. In some regards Fukuyama has already faced much of this criticism preëmtively3, but somehow misconceptions still abound. I agree wholeheartedly with Kojéve’s experience:

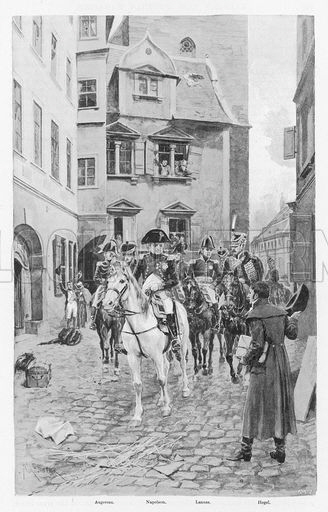

Observing what was taking place around me and reflecting on what had taken place in the world since the Battle of Jena, I understood that Hegel was right to see in this battle the end of History properly so-called.

I have written this text both to convince the readers that this is the case, but also to work through my own thinking on the topic. I will try and cover some major events and areas of the world who one might see as counterexamples of the thesis. But first we must make clear what History is and is not.

What is meant by the End of History?

History seems quite straightforward as to its definition, most in the western world had it as a subject for several years and so think they have a through understanding of the term. When seen through this lens it is mostly defined as the study and documenting of events in the past and perhaps on how they influence the future. But in the Hegelian sense history is more so seen as the trajectory of human consciousness toward absolute knowledge and self-consciousness. I am not surprised that most people, even academic scholars and subject-matter experts, misunderstand this point — Hegel is not very widely read and his concepts are mostly known through the interpretation of others. The end of history appears when this absolute knowledge is realized and actualized in the geist of the world. In Hegel’s view the trajectory this first took was through the Greeks, Christianity, Lutheran Protestantism, the French Revolution, and finally described at Jena by Hegel as Bonaparte marched through it4. Napoleon and the society he represented was however merely the vanguard of world-history, and there was of course still the work of implementing it. This will likely take the appearance of the graph for the function \(f(x) = 1 - \frac{1}{x}\), with the world in a continual process to reach historical culmination. But this still does not mean that authentic historical action is possible, it would merely be bringing the other parts of the world in line with the most developed historical position; it is an extension of width rather than in depth. Post-historical society is one in which the economic activities of man are most prominent, rather than the drama and spectacle of struggle and war. As such it can not be preöccupied with conflict with other post-historical regions; it is bad for business after all. Society revolves entirely around the ideas of maintaining humanity’s happiness. This should not be misconstrued as a regretful development — a lack of suffering and pain in the world is a noble goal. But it is the reality that we no longer have anything to strive toward beyond hedonistic happiness that defines post-historical man. Things such as the impending crisis of climate change is nothing more than a threat to “our way of life”, and a threat of such a nature is the greatest threat post-historical society can face.

History then did not end in 1989, and it is with that I agree with the critics of Fukuyama. Instead in ended almost 200 years earlier, in 1806, when the ideas and processes that create the final shape of society were first identified. When one makes this claim it becomes obvious how laughable counterarguments of “well why did the Ukraine war happen if history ended?” when events like the first and second world wars are both seen as entirely post-historical, even by people who lived through them like Kojéve himself. Events of large material importance can (and indeed must) occur, and a country does not have to deny the end of history to maintain a large military force. But this force is oriented principally externally toward those regions of the world where society has not reached the same level of historical development, whether that be North America in 1812, Eastern Europe during the cold war, Iraq in 2003, or the Russian Federation today. Those societies already firmly established within the post-historical framework are no longer a threat to other post-historical societies. The strange phenomenon of the democratic peace may very well have its solution in this perspective, where the Stewartian definition5 of democratic or elective states can fully replaced with those regions of the world where history has ended.

According to Kojéve society in a post-historical time is structured through “the universal homogeneous state”. What this state looks like differs depending on one’s interpretation, but all of the major illustrations of such a state6 are fundamentally attempts to impose what is strictly a philosophical identity on to an empirical political reality. But what seems to have occurred is rather distinct from this, our philosophical development has occurred not in parallel with political development but entirely separately. It remains unclear if political development will in time “catch up” with our popular consciousness, as with how the ideas of the enlightenment spurred political development in 1848 and continue to underpin contemporary events, or if this combination of philosophy and politics are fundamentally still compatible. The largest crack in this status quo that I perceive is arguably the environmental movement (and its reactionary counterpart) if any.

I should make clear that I disagree with Fukuyama’s view of a liberal, democratic, free-market west as the uniquely final historical position. Although there is a clear correlation between the post-historical regions and these qualities one should not mistake the sale of ice cream as the cause of drowning. Instead this universal homogeneous state exists not as a state as used within the context of international relations, a political unit with a defined territory and nominal sovereignty over it, but a state as in a state of affairs. The universal homogeneous state is a shared lived experience and way of thinking about the world around one self7. It is especially prevalent on the banks of the northern Atlantic ocean, in Japan, South Korea, and Oceania, regions of the world uncontroversially seen as part of Fukuyama’s post-historical world. But it is equally present in regions such as Shanghai, Moscow, Cape Town, and São Paulo. The reverse is also true. The United States for example has many areas that are not part of this post-historical world, even though the US as a whole is firmly post-historical in nature (the case is also true for much of Europe). One can draw a rural-urban divide here, but that would still not be entirely correct — many urban areas still have not reached the end of history, and many rural areas have — but one would likely still see a strong correlation. Why urban life creates the conditions for post-historical man I will not describe here, but will cover at a later time.

It is however the case that this state is not merely a fixed set of philosophical conditions paused in time. Keeping in line with Hegel the self-consciousness of the individual is distinctly created in opposition to the other8, and is in a continuos process of recreation (in both the literal and figurative senses of the word) that characterises post-historical society. The inter-subjective forum where this process takes place is the internet. Most of the computer’s major impact has been not in the fields of mass-manufacturing or administration, but in the spread of ideas and media’s increased intensity and presence within our daily lives. It is this shared experience of mankind’s manifestation in the digital realm that bind’s the world’s populations into a single coherent whole; into a homogenous state of being. Preceding digital computers the homogenous state was of course still present, through the shared human experiences and means of communication of earlier times. But this was broadened — binding more and more of the world’s population, space, and time into it — by the telegraph and the transistor.

The end of history is then not the achievement of any set of material conditions (the absence of war and hunger) nor is it the culmination of political development throughout time. It is the philosophical realization of a given identity, of a set of values, and an understanding in self-consciousnesses on the scale of humanity as a whole. We will now chart the current state of this weltgiest as it appears to us in the first half of this decade. To begin we will cover the grand expanse to the east of the European subcontinent.

Russia

We begin with Russia not just because it is, here in Sweden and in Europe as a whole, seen as the unmaking of what they see as the greatest achievement of the post-historical world: the long European Peace since 1945. But, as we have already covered, post-historicity does not mean the end of wars, the redrawing of borders, or of major historical events. In fact, conflict must occur while there are still parts of the world who have not reached the end of history. Russia feels provoked into action and therefore must act. It is a state that is so developed that the state encompasses all — this is nationalism — but it has yet to achieve the contradiction between the state and the individual. It is this key change that Napoleon embodied, and so it is not impossible to do through authoritarianism, but it may also require democratic reform. Until then the state is what will drive historical development, pure economic growth or citizen movements will be unable to act in this environment. It is then this feeling that the Russian state has (or is at least interpreted and anthropomorphized as having) that makes this interesting from a philosophical point of view, that drives its foreign policy goals.

But this is not a mere conflict over Russian sovereignty in its “near-abroad”. In Russia this is framed in “civilizational” terms, where the Russian civilization is distinct from the western-European one, just as the Chinese or Hindu one is. This means that Russia must identify itself in contrast to the rest of Europe. It still gains its identity from its relationship to the other and can not maintain a disparate identity that makes peaceful relations possible. It must see itself as in conflict with the other as long as it is still a master in the framework of Hegel’s master-slave dialectic. The collapse of the USSR was a humbling of the Russian civilization within these terms, but it was not defeated in the sense that it surrendered out of a genuine fear for death. This fear is what drives the continually conflict-prone master to become a slave, and it is only the slave who is capable of fully realizing her self-consciousnesses and progress history. Russian aggression must therefore occur before it reaches historical fulfilment, it is still a master in search of another master that can recognize it. But it is not merely enough for Russia to back down against the west of Europe, is must feel a genuine dread throughout its nation. But this is also not something that can be imposed from abroad. Franco-German tanks rolling across the Red Square will strike fear into the hearts of Russians yes, they may become even more bellicose and struggle for revenge. Instead it is a feeling and historical process that must come from within. The Russian consciousness must be transformed by their own volition to be of this nature, just as what happened in most of the Soviet satellite states after the cold war.

This is not a process that one can expect to come quickly, but it is at the same time hard to say if it will take a long time. It will occur gradually, and then suddenly. Until then Europe, and the rest of Russia’s neighbours, should be prepared for conflict with it. It is not a contradiction of post-historicity that Finland should arm itself for war with its much larger possibly belligerent neighbour; as long as that neighbour is itself not another post-historical state.

The United States of America

The second major development seen by many as a counterexample against the end of history are the developments in the United States of America; more specifically the election of Donald Trump. But the question that needs to be asked is what Trump’s behaviour is actually symptomatic of. He has threatened annexation of post-historical allies such as Canada and Greenland; does this not show how the assumption that post-historical states do not have to protect themselves against others of their kind is wrong? But remember, the nature of history is not of a political nature, but of a philosophical one. Does Trump have any ideological or idealist qua idea motive for his actions that contradict those of the rest of the world? I do not think he does. He of course utilizes different techniques to achieve his aims, and may desire power for power’s sake, but these are not in and of themselves a goal. Really Trump has the same goal as the rest of us, the maintenance humanity’s happiness. He may fail at doing so for a multitude of reasons, but it does not mean that America is in a conflict (in the philosophical sense) with Europe or Canada, just as the US was not in conflict with the UK and France in 1956 despite actively undermining them and the presence of hostile rhetoric between the two camps.

Trumpist America lacks an ideological driving force of what the world should look like and is therefore incapable of historical action. It leaves the individual in the same position as liberalism, as the citizen entirely involved in, and yet at the same time wholly separated from, the state. MAGA is pure populism, and in many ways itself an example of post-historicity. It is the juxtaposition of the individual against the other, against a nebulous grouping of the woke. The individual is seen as simultaneously part of the greater whole in a collective labour to improve society, but at the same time promoting the ideals individualism and freedom and a hatred toward those opposed to the Trumpian project, whatever it may be. Trump’s authoritarian tendencies also do not discredit the thesis; the very vanguard of history was originally realized through Napoleon Bonaparte, a populist general who performed a military coup and whose rule was by no means democratic.

The developments in America then do not conflict with the end of history, they are merely another manifestation of its predicted behaviour, and in some ways even a strong example of the thesis itself. Exactly what the nature of authoritarianism and fascism is in the post-historical environment I will not endeavour to explain here however.

The People’s Republic of China

I hope that it has become clear that while I disagree with Fukuyama’s critics on the basic reading of him (or lack thereof) I am also not a clear-cut supporter of his ideas, especially in their most popular form. In an interview with Foreign Affairs Fukuyama has stated that the “single” counterexample to the end of history is the rise of the People’s Republic of China, and the level of economic growth and prosperity it has achieved while under the auspices of a socialist one-party state. But there are two main factors that have allowed this apparent contradiction to flourish: the fact that Fukuyama is wrong about the need for liberal democracy to build a prosperous economy and the fact that the CCP has adopted the very strategies proven to be successful in the west.

What causes economic growth is a question that is not easy to answer, if it was then every country would do it. But there are general assumptions to be made through correlation that allows us to see this from an interesting point of view. Since the beginning of the industrial revolution every school of economics has had to make its argument for why it occurred. It was such an explosion in economic growth and activity compared to pre-historical times that nothing in human history has had a similar impact on the condition of the human population — and the rest of the living species in the world. Trying to contend these intellectual giants is then an incredible feat of hubris, and I shall not seriously argue that a question of such magnitude can be answered easily. Nevertheless I believe that there is a generally impactful variable in stability. My ideas on this topic are heavily influenced from listening to the recipients of the 2024 Nobel prize in economic sciences9. In this line of thinking, stability (both in the form of a lack of conflict and in an awareness in “how things are done”) are hugely important in determining the levels of prosperity in a country. In this manner democratic states are not only wealthier because some of them have had a history of colonial exploitation, but also because democracy inherently has rules and regulations and tries to punish those who break them in predictable ways. A philosopher king who rules by decree, no matter how benevolent or skilful, may change either his mind or “the rules of the game” abruptly, bringing a sense of insecurity into any venture. What Fukuyama calls China’s “institutionalized autocracy” brings this factor into play in China. Since there was no absolute ruler, only the nebulous institution of “the party”, change could not occur at the whims of any particular person, and so companies and individuals could trust that they could foresee or understand changes made. This is the stability necessary for a market economy to work efficiently, even if the “rules of the game” as set are flawed and imperfect. Changing them should still be done of course, but predictably, transparently, and accountably. It is in manner that economic successes can be explained independently from liberal democracy or their ideals, such as the formal rule of law. As long as things occur as people expect they do, they can continue doing business.

But the key is that China has adopted a market-economy, albeit perhaps of a dirigiste kind. This is in line with the idea concept of socialism with Chinese characteristics, where China’s largely rural, poor, and agricultural society would/is not capable of attaining socialism and communism, largely a return to orthodox pre-soviet Marxist thought where the origin of revolution would be in the industrial heart of the world economy; in Germany, the United Kingdom, and France. What the CCP is doing is then not contradictory in the slightest according to ideology, it is only wrong to call it socialism. But this is mere pandering to ideologues, in reality I do not believe the CCP leadership has any intention of returning to the socialist policies preceding Deng Xiaoping (邓小平). Mark Fisher was correct in observing the stagnation in politics following the collapse of Soviet empire in Capitalist Realism, with the introductory chapter famously using the Zizekian/Jamesonian quote of “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism”. Capitalist theory and practices have become so engrained in the consciousness of the world that it is no longer possible to move to another alternative10.

Both ideologically and economically China has become allied with the west, but China is in many ways post-historical in its philosophical sense as well. I intend to examine both the extent and nature of this more carefully when travelling to the PRC later this year, but Chinese society is equally perpetuated in the hedonistic joy of society. This is of great trouble for the CCP, whose ideology is based on a continued struggle toward communism. Instead of caring about the historical development of the proletariat the Chinese population is troubled with post-historical issues. They wish for stable iron-rice-bowl jobs, fleeting consumer goods, and the ever-continuing flow of entertainment supplied by services like Douyin. Life becomes a hedonistic maintenance of happiness and joy, just as it has become in the other post-historical regions of the world like Europe and Japan.

Conclusion

My hope is that this has been an illuminating coverage of some of the main criticisms of the end of history, and that I have dispelled any notions of history “restarting” or that we have merely been on a “holiday” from history since 1989, with the so-called holiday ending either in 2001 or more recently. If you have any other major counterexamples I would be glad to hear them, since many of these major ones I have here covered are quite elementary — with the major issues merely being a gross misunderstanding of what is being discussed. I shall end with a quote by Kojéve that showcases the nature of post-historical society:

It is precisely to the organization and the ‘humanization’ of its free time that future humanity will have to devote its efforts. (Did Marx himself not say, in repeating, without realizing it, a saying of Aristotle’s: that the ultimate motive of progress, and thus of socialism, is the desire to ensure a maximum of leisure for man?)

❦

Footnotes:

The title of this post is a reference to that article. Instead of merely asking “The End of History?” this post argues definitively that the end of history has occured.

Stéfanie von Hlatky and Michel Fortmann, “NATO Enlargement and the Failure of the Cooperative Security Mindset,” in Evaluating NATO Enlargement (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 546.

As early as the introductory paragraph of his article Fukuyama states:

The past year has seen a flood of articles commemorating the end of the Cold War, and the fact that “peace” seems to be breaking out in many regions of the world. […] If Mr. Gorbachev were ousted from the Kremlin or a new Ayatollah proclaimed the millennium from a desolate Middle Eastern capital, these same commentators would scramble to announce the rebirth of a new era of conflict.

Is this not what is happening at the moment? There is of course a new era of conflict, but does that mean that the historical processes playing out over time are not there?

I can’t define it but I know it when I see it.

For the right-Hegelians it is the rigid authoritarianism and pietism of the “Prussian virtues” that takes this place, for the left-Hegelians the classlessness of communism, and for Fukuyama the liberal world order.

And in the Hegelian sense thinking can not be disentangled from action.

From the Phenomenology:

[…] in fact self-consciousness is the reflection out of the Being of the sensory and perceived world, and essentially the return from otherness.

That being Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. I am aware they did not technically receive a Nobel prize, but instead the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, but find the distinction unnecessary.