Exponentials and Artificial Intelligence

Introduction

The subject of artificial intelligence (AI)1 is one that has become hotly debated in recent years. That the growth of AI’s capabilities has been partly driven by what is becoming increasingly clear financial engineering. These problematic elements has created a stark division of opinions that can generally be subdivided into the following categories:

- The masses. A large, indifferent group who use LLMs in different capacities — stretching from the most common not-at-all to daily. Their unifying character is that they primarily do not think about the philosophical, technological, political, macroeconomic, or in some other sense structural impacts of quick AI growth.

- The Luddites. A highly critical and hostile group of artists, environmental activists, reactionaries and software engineers who prefer “hand-crafted” code. They are much more plugged in to the conversation than the every-man, but are at the same time reactionary in the Newtonian sense, explicitly denouncing any AI advances and proclaiming that AI will not be relevant after the inevitable popping of the bubble.

- The Doomers. Strong believers in strong growth in the capabilities of AI models, but also worried that humanity’s collective ability to control them will grow slower than the aforementioned capabilities. Makes up the majority of the AI-safety community.

- The Optimists. This group believes that not only will AI growth be fast, it will also grant mankind gifts that surpass all that humanity has achieved before, and we will hopefully live in som form of Fully Automated Luxury Communism.

I am not firmly enmeshed in any of these camps. I am too well-informed to be a part of the uninterested masses, and in some ways am more positive about the use-cases of AI than many others (although I do also do not reject the label of luddite either). On the division between “optimists” and “doomers” I find that both are often heavily separated from reality, and in many cases not well-read outside the fields of science-fiction (and perhaps computer programming). This is an attempt to inform these latter groups.

One of the favourite subjects of AI discussions are those of exponential growth. This is usually framed in some way that sets a “before” and and “after”, during which AI gains the ability to recursively self-improve and effectivise the manufacture of goods and services as well as the large-scale automation of R&D. I am a strong believer in the long-term ability for different AI models to improve all of these fields, but believing in exponential growth means that one has to face the reality of the costs of such development.

Human Development

It took humanity roughly as long to go from using bronze swords to iron swords (3300-1200BC, roughly 2100 years) as it took to go from iron swords to gunpowder (1200BC-904AD, 2100 years) and from then it was only one millennium until we had the ability to destroy ourselves utterly with the invention of the atomic explosive (1945, 1041 years after the military use of black powder). The growth in technological capacity is already an exponential one.

The growth in computational potential is famously also exponential, and in many ways it is the driving force behind the capabilities of large language models. But increases in energy efficiency and computational speed are harder and harder to come by (Dennard scaling has been gone for 20 years now). This does not mean that growth in computation is likely to stall, but instead it means that more and more resources and inventions need to be produced in order to maintain the same rate of exponential growth (since the integral grows faster than the absolute value above it). Lithography machines are a famous example of this; likely the most advanced machines that humanity has yet to create, they consist of individual parts that are incomprehensibly precise2.

I feel compelled to quote Alexis de Tocqueville; There are two camps consisting of those who believe AI will dramatically accelerate technological development and those who believe it be a mere fad. “It is to be presumed that both are equally deceived”. I believe that AI will be a necessity for continued technological growth as the barriers are continuously rising, but that a very quick (less than half a decade) transformation is very unlikely. Many analyses of an AI-powered economic boom predict yearly growth rates in the mid-101% (~50%), but often also mention the theoretical doubling rates of insects or bacteria3. But these latter examples only double very quickly under very unique situations with very large amounts of resources. To me this seems like a classic misunderstanding on the structure of human development.

That invention is the driving force behind development has been a dominant thought since the enlightenment. But one should not underestimate the importance of a more organic and more diffuse form of development. The economy of the PRC, or of the four Asian tigers, doubled incredibly quickly, but when it did so it required enormous amounts of resources. The industrialisation of China needed huge quantities of steel, concrete, and energy to construct railways, highways and urban dwellings. The physical mass of this puts an upper bound on the speed for growth that a superintelligent AI can not fix.

Doubling the number of factories requires a large increase in construction-related steel production, and that requires an increase not only in logistics, but also in the exploitation of resources. A delivery of iron ore takes a month to travel by sea (one of the most efficient forms of transportation) from Australia to Shànghăi (上海).4 Delivery of construction equipment also takes an insignificant amount of time. The Abundance-argument regarding red tape is of course valid, and there areas in which improvements can be made in western economies, but one still needs to keep in mind an analysis connected to the situation on the ground.

Richard Danzing’s recent paper on cybersecurity and AI stresses an important fact when it comes to national security, that AI is here now and needs to be continuously integrated into the (American) national security apparatus in order to avoid a “Maginot moment”. This rings true for economic development as well — because the nature of war has become more and more industrial as the state and the economy has grown.5 Waiting for a potential “AGI” to be invented before applying it to the economy is akin to (to take inspiration from Danzig) waiting to discover the mythic city of El Dorado before taking advantages of the discovery of America.

The (Fourth?) Industrial Revolution

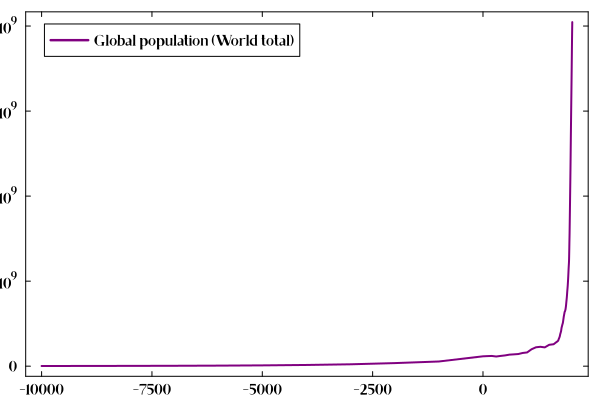

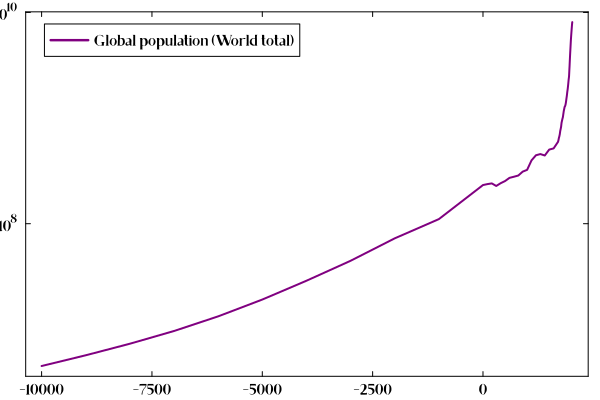

A particularly obscene phrase (although it seems to have been fallen slightly out of favour) is the statement that AI will in some sense kickstart a “fourth industrial revolution”. In fact, there has only been one industrial revolution — and we are all still in its midst. To showcase this, here is a graph of the world’s (human) population6:

Here it is again, but this time with a logarithmic y-axis:

It is clear that, while the population has generally been increasing steadily, there was a sharp inflection point (that can be clearly made out even in the second graph) some time in the 17th century, i.e. the industrial revolution. This development has not wavered, an despite demographic decline in Europe and east-Asia will likely continue until the end of the century. At that point, even if the population decreases faster, we will still be so unfathomably greater in number than we have been for practically all of human history. The power of industrialisation is awesome qua the sublime.

The division of industrial revolutions typically do so by focusing on the specific “driving” technologies. But those technologies do not come out of nowhere. They are needed, invented, applied, and (through their application) they drive new needs. The shape of technological growth (since the industrial revolution that is) appears in some ways similarly to the following function:

\[ g_t(x) = c + \sin{x}, \hspace{1em} c > 1 \]

There is always some underlying R&D (in the literal sense) going on,

and it in turn prompts new developments to begin. Because the above is

the growth of technology, and because the value of sin never goes

below -1, there is never any regression in technology (as I am aware

of there has never been, apart from the Bronze age collapse). The integral of this then becomes

\[ G_t(x) = cx - \cos{x} \]

where \(cx\) continuously keeps going up, and mirrors in this sense the continuous advance of technology. There has been rapid change for a long time now — almost 300 years. Each generation that has lived through this development has had to grapple with its consequences. The field of political economy grew out of not just an attempt to control and steer this growth, but also an attempt to try and attempt how it happened in the first place.

Smith did so using the analogy of the pin factory to show how increasing markets made possible by international shipping, steam engines, and empire led to an increased division of labour and therefore an increase in productivity. Marx in turn tried to describe this by framing it as a consequence of primitive accumulation (through the expropriation of land) and capital’s ever-increasing needs for growth. In fact, there has not been a decade since the late 1700’s that has not been revolutionary in some way.

Conclusion

To say that the next decade will be transformative is an easy bet to take. We humans like to think that the world will stay the same forever, but our increasing industrialisation means that that will likely never be the case again. It seems strange then to write a post arguing against rapid change. But that is precisely the problem we are posed with — because we see the world as static we do not notice how much it is changing.

When we are presented with a technology as all-encompassing as AI it is entirely rational to see it as upending the world as we know it. But the world has seen — and is currently seeing — transformations of equal (if not greater) impact. The conversation around AI is stuck with its blinders on, just as those who (mistakenly) saw crypto as revolutionary did not focus on the broader technological change of the planet. We must therefore enlargen our view to encompass all these aspects in order to adequately think about how technology will impact our lives.

Footnotes:

I usually strongly dislike the term artificial intelligence, and generally try to avoid the term. This is not because I hold any beliefs akin to “AI is neither artificial nor intelligent”, but because I find the term reductive and imprecise. It refers to a great number of different techniques and technologies, and thus talking of any specific “AI growth” is often misleading for those who do not understand the intricacies of machine learning. For this reason I generally prefer LLM (large language model), but will in this case use the more broader definition.

The mirror elements in EUV machines have errors of 1mm if extended to 1000km (“The size of Germany”), or 0.3nm over 30cm. Source.

Preparing for the Intelligence Explosion by William MacAskill and Fin Moorhouse.

Modeling the Human Trajectory by David Roodman.

The bulk freight of travelling from port-to-port is perhaps the most efficient part of steel’s logistical path. It then has to be transported numerous times to be refined, and then shaped into lots of different shapes before being made part of countless machines, constructions, or devices. As goods are transported to increasingly more unique locations, the cost (and correspondingly time) goes up dramatically. This is known as the last mile problem.

Much can be discussed on this topic, and I hopefully will do so some time in the future in a separate piece.